Paperback - eBook - Hardcover

Audiobook

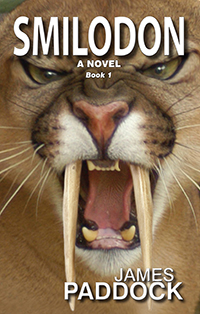

(Sabre-Toothed Cat Book 1)

Chapter 14

The following day, Saturday, one week after my arrival, I awake to the sight of water dripping in front of my window. The sun is shining. It was well after 2:00 a.m. before I fell asleep. It’s now 10:00. I’m curious if the water dripping means the temperatures have risen above freezing. Although I’m anxious to find out, there are other things I want to do first.

After the shower and shave, I make some breakfast – bacon, eggs, toast and coffee – and retrieve the CD from where it is secluded. I make my entries in my secret file, send it off to Catalog.com, and then burn it to the CD.

I feel rather stupid, actually more like phobic. I’m afraid of people peeking at what I write, maybe afraid that the killer will find out that I suspect something. I try to deep breathe the fear away, but it’s no help. The tightness in my chest makes me wonder what it’s like to have a heart attack. I put away the laptop, which makes me feel a little better, and then stand at the window with my third cup of coffee. I know I should stop at one, but there are days, too many days recently, that require several more. This one will not be my last. There may even be another pot.

The bright day has gotten brighter and the world is obviously melting. How long will it take to melt this much snow? How far away is the real Spring? There is a feeling in the air, and it’s not a joy at approaching spring. Rather, it’s ominous, almost apocalyptic. I want to slap myself across the face, knock such feelings of doom out of my head. But I also know that is useless – knocking away the feelings that is – as useless as turning away from an approaching tornado in hopes it will go away. When I get these impressions, they always mean disaster; more often than not that someone in close physical proximity to me is going to die. I can seldom put my finger on who, how or exactly when. One such time was when the girls were very young, babies actually, and we were all together waiting to cross a street in downtown Dallas. The weather was mild and many people were out. I was carrying Rebecca. Tanya was pushing Christi in the stroller. The light changed. People moved and then the feeling came over me. Often times it eases on me over a period of hours or even days, kind of like what is happening now, but this time it hit me quickly. I received no visions, no words of warning, just a feeling, a horrible feeling that I know means something bad will happen and I cannot do a thing about it.

“Stop!” I yelled to Tanya. I never have any idea if stop, or run or lay on the ground are the right things. Stop is instinct in a fearful situation. She turned around and saw the look on my face, realizing instantly why I said stop, no more able to do anything about it than I was. She picked Christi out of the stroller and then stood close to me and waited. People walked around us. She looked north. I looked south. We waited, waited . . . waited until she said, “Maybe this one was nothing,” and then said, “Oh my God!” When I turned around she was looking up and backing into me. A girl, not much older than a child, was inching her way along a window ledge, five floors up. We learned later she was only thirteen years old. A head poked out the window and yelled words I couldn’t make out. The girl turned, slipped, dropped onto the ledge and then bounced away and plummeted to the sidewalk not twenty yards from us.

These are the kinds of feelings I get. Very frustrating feelings, as I can never do anything to stop whatever it is that is about to happen. It’s this kind of feeling I have now, however I realize this one has been coming on me for several days. At the time I thought it had to do with the death of Doctor McCully and the surrounding tension and gloom. I am now readily aware that it did not. Why I don’t feel the approach of all bad things, I don’t know. I did not sense a thing before McCully was killed.

So what is it that is about to happen? When? Today? Tomorrow? Usually at this point it’s no more than a day away, or maybe hours. However, I could be off kilter with everything else I’m currently worried about. It could be anytime in the next few minutes or the next few days.

I need to shake it away. I can’t stand here and stare into white space until something happens. I decide to go in search of Lance or Aileen, so I pick up the company directory of phone numbers – it makes up one page – and then . . .

. . . the phone rings.

I’ve never heard it ring before. My feelings don’t currently correlate with the phone, so I pick it up.

“This is Zach.”

“Hi, Zach. This is Aileen Bravelli.”

I’m surprised into silence.

“Zach?” she says. “You still there?”

“Yes . . . Sorry. I . . . ah . . . wasn’t expecting . . .”

“If you’re in the middle of something I can check back with you later.”

“No. I’m not doing anything. It’s just that this is the first time my phone has rung since I’ve been here. I kind of forgot I even had one.”

She laughs. “Sometimes I would like to just unplug it for good.”

“It’s strange. I was just about to give you a call.”

“Oh! About what?”

“I want to apologize.”

She doesn’t say anything.

“Can we get together?” I add. “Meet somewhere?”

“Have you had lunch yet?”

“I had a late breakfast.”

“Oh!”

“But if you’re cooking . . .”

“Come on over. I’m just doing soup and sandwiches. Bring your favorite beverage.”

My feelings of doom are momentarily forgotten. My favorite beverage is a beer – but not for lunch. I refill my coffee mug, grab my notebook and head out the door.

Aileen’s apartment is identical to mine, only reversed. Everything that is on the right in mine, is on the left in hers. The décor is a lot nicer, however. Curtains and vertical blinds frame the window. Several huge potted plants take up spacious areas. Many smaller ones take up tables and counters. I touch them to see if they are real. They are. I’m impressed. I tell her.

“I’ve always had a knack for plants,” she says. “I must have been a florist in my previous life.”

“Or a horticulturist,” I say “Maybe it’s what you are meant to do in your next life. You will be a horticulturist and find you have a knack for understanding old bones. You will say then you must have been a archaeologist in your previous life.”

“I’m not an archaeologist. I would assume with all your research you would have figured that out by now. I’m a paleontologist. So many people get that mixed up.”

Apparently I just irritated her. “Sorry. That must be a pet peeve. Kind of like my being called a reporter. I’m a journalist.”

“A photojournalist at that,” she says.

“Yes.”

“Certainly a lot more than just a reporter.”

“You’re making fun of me. How about we call a truce on our pet peeves. The soup smells good.”

“Truce.”

I sit at the counter with a chicken salad sandwich and a bowl of strange looking soup. I eye-ball it for a minute before trying it. It tastes delicious. “Very good,” I say.

“My grandmother’s recipe.”

“What is it?”

“Never got a name with it. Grandmother called it, ‘my soup.’ I call it Grandma’s Gumbo. I don’t tell anyone what’s in it. I’ll put it in my will to my children.”

“You have children?” This surprises me. In my vision of her during our encounter in the library, and my read on her now tell me there were no children. How could I have missed that?

“No. But I will someday.” She looks at me. “What are you smiling about?”

I laugh, a bit embarrassed. “It’s just that I thought for a second I miss-read you. I didn’t picture you as a mother.”

She chews on her sandwich for a few seconds. “Your read on me. How did you do that?”

“One of my talents. I really don’t know how I do it, but I am almost always accurate.”

“Can you do it with anyone?”

“No. Sometimes only little visions, or thoughts come to me. I don’t know which to call it, visions or thoughts. Sometimes there is nothing at all. I’ve thought about that a lot – what is the difference in people that I can sense some things, but not others? It has to do with a person’s aura and how it interacts with mine. I can read emotions in the aura when it crosses mine. It’s sort of like when you pass a wire through a magnetic field. What I get are visions.”

“Aura. Hmmm.” She quietly spoons her soup for a time. “You said that was one of your talents. You have others?”

I spoon the last bit of soup from my bowl. I didn’t realize that I would be that hungry after a late breakfast. “There is one other I would rather not have.”

“A talent you don’t want?”

“I can foretell tragedy.” I suddenly wonder why I am telling her this. These kind of talents are things that label one crazy if people find out about them. Relatives are suddenly very busy or are never home. Friends are instantly not your friends anymore. Weirdoes start searching you out to find out what kind of doom they should be expecting. When I moved from San Antonio to Dallas to take the job as a copywriter, I decided to not tell anyone about my abilities. Tanya and I were married several months before I told her. She didn’t believe me at first. Long before the girl fell to her death on the Dallas street, Tanya had become a believer.

Why am I sharing it with Aileen, someone I hardly know?

“Interesting,” she says.

She moves her bowl and mine to the sink and rinses them. I finish my sandwich and shove the plate toward her. While she cleans up I open my notebook and write some words.

“You’re taking notes?” she says jokingly but I sense the irritation.

“I write down interesting words.” I turn the notebook so she can read it from her side of the counter. “See.”

She looks down while drying her hands and reads what I wrote.

Do you know there are video cameras and microphones

in our apartments?

“Interesting,” she says and then turns and continues to putter in the kitchen, putting things away and straightening. Just when I begin to wonder how much of this video thing she knows about, and begin to suspect that she may be one of those monitoring me, she says, “Lets take a walk through the gardens.”

Her eyes meet mine. “I’d love to,” I say.

“Wolf is not here,” Aileen tells me when we step into the first of the two dome-covered buildings. “His mother is gravely ill. He has returned to India for an undetermined time.”

“Undetermined time?” I say.

“Until his mother dies, or gets well. Here is Thomas, however.”

Thomas Holm appears as though from nowhere. “Mister Price. Miss Bravelli. How you do?”

“We are doing just fine, Thomas,” Aileen says. “Mister Price wishes to walk through the gardens and observe the animals.”

“Oh, yes. Do please.” He is excited. “We go this way. Follow me.”

“We can find our way, Thomas. It’s not so big we could get lost.”

“Yes, yes, but quiet must be.”

“I know, Thomas. We’ll be quiet. Don’t worry. You go back to work and let Mister Price and me observe the Sabres. This is part of his research and he doesn’t need a bunch of us hanging around him all the time. I’ll keep an eye on him. OK?”

His eyes dart between Aileen and me, apparently not sure what to do. I have a hunch they don’t ever let anyone in here alone. Wolf probably runs a very strict shop. He left Thomas in charge and now Thomas feels like his authority is being challenged.

Aileen puts her hand on his shoulder. “Don’t worry. I won’t tell Wolf. And besides, Mister Price and I are working together now on the book Mister Vandermill wants to publish. We are collaborating. We’ll eventually interview you as you will probably have an entire chapter.”

“Oh!”

“Thank you, Thomas.”

“Yes. You go now.” He nods he head. “Quiet be, please.”

As we step through the gate, I glance back. Thomas is still standing as we left him, a hand on the shoulder where she touched him. I don’t like the impressions I get, nor the sudden rise in pressure in my chest.

We walk along the path until we come to the place where I observed Duchess the week before. We stop but the big tiger is not in sight.

“We can talk,” Aileen says, “but we’ll have to whisper.”

“Because of microphones?”

“No. Wolf is very strict about noise for a reason. We want to watch them as much as possible without our intrusions. Not so much Duchess here, and the other Bengals. They’re used to humans being around, although if they see or hear us, they go into the bush. That is their nature. We wish to observe the sabres in the purest wild. The reason for the one-way glass. Even when we are there they don’t know it.”

“They sure knew something was up when I got excited over that snake.”

“I think the only reason Wolf didn’t pull a knife and slice your throat right on the spot, was the reaction from the cats.”

“Really?”

She looks at me and grins. “Come on.”

“Are there microphones?” I ask.

“No. Just cameras. And they’re to observe the animals, not us. But just in case, it would be a good thing to be whispering.”

I follow along for a while, looking into open areas for signs of the tigers. I never see one. “So, what is with the cameras in the apartments?”

“Victor claims it’s for the protection of industrial secrets.”

“But you’re not so sure of that.”

“No.”

“You think he’s afraid someone will steal the toilet paper?”

She laughs. “Maybe you’re in the ballpark. I don’t really know. I think he is just a micromanager, what you said he was not.”

“True, but I have only met him once.”

“I think he is a closet micromanager. He does it without anyone really knowing he does. He wants to know what is being said and done behind his back so he can control everything. He hires people to do what he wants, and pays them well. He is certainly not cheap. I don’t believe there is a decision made in this company that he hasn’t already given his OK to.”

“That’s why you wouldn’t marry him,” I say.

She stops and turns to me. “That book I gave you? That’s his. It was his idea and being young and naïve, I wrote it for him. I was excited about the notion of getting my words published, but he managed every goddamn one of those words, and got me into his bed as a bonus. I’m not proud of it. As a matter of fact I hate myself for it, especially after doing it again when I thought he agreed to not hire you. Sometimes I’m an idiot, and just as naïve as I was ten years ago. He used me again.”

“His ex-wife,” I say. “Did she find out about you?”

“I don’t think so. She got fed up with his control of her, decided she needed to find her own life. She also hated it here. She stuck out three winters before she quit. She’s doing well in Atlanta. We talk now and then.”

“You’re friends then?”

“Yes. Good friends.”

We come to the end of the garden, pass through the park-like area, and then enter garden two.

“Now is the time to be exceptionally quiet,” she says. “I want to ask you something first, before we go through the door.”

I look at her and wait for her question. It occurs to me how beautiful she is. Not that it hasn’t occurred to me before, but it kind of washes over me this time. I feel myself being sucked in by it, find myself wondering what it would be like to feel her lips on mine. I back up a step. “What’s your question?” I need to stop it – the feelings.

“You said you can foretell tragedy, that it’s a talent you don’t want. What did you mean by that?”

It’s a serious question. I sense she has no thoughts that I’m crazy. I feel safe. “I sometimes can tell when something is about to happen – not happy events – tragic events.”

“Like what? Give me an example.”

“The first time I remember was when I was eleven years old. I’m sure there were times before that but this was when I became aware that I knew before it happened. I was at a high school basketball game watching my brother. Suddenly I had a feeling that something awful was about to happen. It comes on me in different ways, sometimes slow over a period of days, sometimes suddenly and there is only a matter of minutes. I didn’t know what it meant but there was an anxiety building up in me. I recall my mother looking at me and asking what was wrong. I told her I didn’t know. It went on for about ten or fifteen minutes. At some point the ball got away and one of the team members, not my brother, dove to keep it from going out of bounds. He landed on top of a girl on the front row and broke her back.”

“Oh my God! And you knew it was going to happen?”

“Only that something was going to happen. Who or what didn’t occur to me. It never has.”

“How often?”

“That was twenty-two years ago. I probably average two a year.”

“What is the worst one?”

I tell of the girl who fell from the window ledge in downtown Dallas.

She looks at me for a long time, as though judging my sanity. “Have you been feeling anything lately, like in the last few days?”

A question I was not expecting. “Yes.”

And then she says something I really wasn’t expecting. “I foretell tragedy as well, and I have been having some strange feelings?”

All I can do is blink at her.

“I first noticed it when I as eight. I was afraid to tell anyone. I tried telling my teacher once but she scolded me for making up stories. I think I told her after things happened instead of before. God it’s good to be able to tell someone.”

This is unbelievable. “I’ve never known anyone else who could do this!”

“Neither have I. I couldn’t believe it when you said it, but I didn’t want to get into a discussion with you about it with the ears listening.”

“How often?” I ask.

“Not very much. Maybe once a year on the tragic stuff. But I do sense other things. A friend of mine won ten thousand dollars in the lottery. I felt that a day before. I also knew of another friend’s engagement before he asked her. The bad things are much more powerful, though. I never sense anything that is going to happen to me.”

I think about that a minute. “That has never occurred to me, but you’re right. I’ve never felt something that was going to happen to me, or my children. I had a slow one creep onto me for three days one time, and then Tanya, my wife, had an automobile accident which put her in the hospital for two days.”

We look at each other for a long time, until I feel the pull toward her again. I step back.

“Amazing,” she says.

“Did you feel anything before McCully’s death?” I ask.

“No.”

“But you have been feeling something lately.”

“Yes. Very strong this morning.”

“Me too.”

“No other clues.”

“Nope. Never are.”

“If we never sense something that is going to happen to ourselves, then you and I are safe.”

“Apparently,” I say.

She thinks for a minute. “Let’s go.”

Inside the sabre’s garden we fall silent.

The path is just dirt. We step quietly for only a few seconds and then stop and look through the thick one-way glass into a clearing. It’s just that – clear. No sabretooth cats in sight. We move on. We pass one more small clearing and then stop at the third, the overlook of the lake where we observed them in their kill and I saw the snake. There is nothing here either.

Aileen points but I still see nothing. She gets her mouth close to my ear. “See where the tree splits. Just to the right, a few feet back, in the shadow. One is lying there.”

I still don’t see it. Maybe that’s because my attention is focused on the proximity of her lips. I want to lean into them, feel them brush my ear. I don’t. I remain rock still and say, “I don’t see . . . “

Suddenly her hand clamps like a vice on my arm and I hear in my ear the words, “Oh God,” not whispered, but uttered low and alarming. I turn my head toward her and see she is looking over my shoulder, up at the heavy wire mesh screen roof. I look up and see a set of piercing eyes set well back from a pair of sabre teeth. We begin backing up. Aileen’s finger nails are cutting holes in my arm.

“Can he get in here?” I ask, as cool and calm as I can be.

Aileen doesn’t say anything. She continues backing, pulling me with her, until we are stopped by the wall. The fear that is on her face has her voice locked, maybe even her thoughts as well. I’m not sure if I can control my own fear but I realize, maybe subconsciously, that one of us has to stay calm. It’s only a glance at her face but when I look up again, the cat is gone. I’m sure they can’t get to us.

I look out at the beach, and the trees where she said one of them was lying. I see nothing. “They’re gone,” I say.

“No they’re not.” Her voice is low, as though someone else is speaking. “Something is about to happen. Let’s get out of here.”

I put my arm around her and we make for the exit as quickly as we can walk. We would have run but we both think that would encourage a chase. Crazy thoughts, I’m sure, but our thoughts all the same. We bolt through the door and pull it closed behind us, rush through the park and into the Bengal garden.

We stand inside the passage that winds through the garden and shake. My heart is racing. I suddenly realize that we have our arms wrapped around each other. He face is buried against my shoulder. “Are you OK?” I ask.

She doesn’t move for a long time. Finally she lifts her head says, “Yes. I’m fine.” We both loosen our grip a bit and she looks up. Not at me but off in her mind, across my shoulder. I begin to understand that most of the fear I felt was not mine, but hers. It’s now dropping away and my own thoughts are shifting from the Sabre garden to her face – a very beautiful face, even up close.

And then her eyes turn up to mine and I feel it. It’s as though someone or something is pulling, or maybe it’s pushing, on the back of my head, forcing me down toward her. I want those lips so badly. I know what they are going to be like – soft and moist, warm and succulent.

I resist. I hate myself for resisting. I hate myself for needing to resist. I hate myself for wanting to not resist.

I don’t hate myself for wanting her.

Suddenly she pushes away, stumbles back two steps and says, “Oh God! Did you feel that?”

What do I say? Yes – No. Admit it or fight it? The internal battle ensues, but the word, “Yes,” spills out of my mouth.

“It happened, didn’t it? Whatever it was, happened.”

I stare at her blankly and then understand what she is talking about. It’s not the animal attraction between us, which is apparently only in one direction, but the feeling of tragedy – the ultimate of tragedy – death – which has been growing in both of us for the last couple of days. I did feel it but I related it to the scare we just got in the sabre garden, and then the overwhelming need to push my face against hers. I feel foolish, and embarrassed.

I look away. She’s right. The growing tightness peaked in the last few minutes and was now gone. I look back at her.

“Who? Where?” she says.

“It has to be close,” I say. “Where is Thomas?”

As if on cue, we both begin walking through the garden. Side by side. Not touching. I wonder as we walk if she felt anything like I felt, or was her mind consumed by everything else? Again I feel foolish. Someone, we are almost certain, just died and I am still going on about my feelings for a woman who is not my wife. We round a bend and in a flash, all thoughts of romantic feelings for Aileen, guilt and anger at myself, as well as the thoughts while looking in the face of a sabretooth cat, go flying out of my head. Straddled over the body of Thomas Holm is Duchess, the largest tiger I have ever seen. She is no more than twenty feet away.

“Do . . . not . . . move,” I say.

Aileen isn’t moving. As a matter of fact I have a hunch she couldn’t move if she had to. I remember reading that there is something about the human face the Bengal tiger does not like. He, or she in this case, attacks from the rear, never from the front. There was a documented case that once while carrying the victim off, the body got lodged in the V of a tree and flipped over, face up. The unavoidable sight of the man’s face forced the tiger to abandon his kill and run into the forest.

I’m praying this is a fact and not just some made-up story by the local people of Bangladesh, or by the author. As a matter of fact, right now, my life, and Aileen’s life, depends on it.

I try to move but my heart is racing and my legs are doing nothing. They want to turn around and run. My mind refuses to let them do that. I finally force a step forward, toward the animal with the eyes at which I am now staring. We are locked in a face down. She lowers her chin, stretches her neck and backs up one step.

“What are you doing, Zach?” Aileen’s voice is raspy.

“Do not turn your back to her. Make sure she sees your face.”

Duchess backs up another step.

“Step forward with me,” I say.

“I . . . I can’t.”

“If your life depends on it, you can.” I reach my hand back without looking. Her fingers touch mine and I stare hard into the eyes of the big Bengal. The stripes of color around her eyes remind me of vanilla or orange pudding as I pour in the chocolate. Thick and thin stripes float in a dirty gray and orange field. The eyes are blue, deep enough to see right into me, and I’m afraid they are seeing my fear and will know that one step forward and I’ll turn my face and run, no matter how hard I try to tell myself not to. She steps back again, and then again, and has now cleared Thomas’s body. She dips her head once more, turns partially away, not yet taking her eyes off mine. I step forward again, pulling Aileen with me. Her hand is fully in mine now, and I am not letting go.

And then Duchess turns and runs off, around the next bend, out of sight.

Now what?

Without taking my eyes away from the last place I saw her, I bend down and feel for a pulse on Thomas. There is none. Never will be one again.

“Stay here,” I tell her. “I’ve got to see where she went. If she returned to her area maybe I can close off the door.”

“No, don’t. If you corner her, she may not be so predictable. We can just back out of here, go out the side door and go around.”

“We can’t leave him.”

“He’s dead. We can’t help him now. Let’s not add our deaths on top of his.”

I think about that a minute and realize she’s right. Get out of here. Let security come in with their dart guns. “OK. You talked me into it.” I rise and back away from Thomas and then hand in hand we walk backwards. “There’s no way she can get around behind us is there?”

Aileen suddenly jerks her head around to our rear. I stiffen. “No,” she says. “No way.”

“Can she get outside?”

“I don’t think so.”

We continue backing until we feel the door, and then we are outside in the cold mountain air. It feels wonderful, for a time. We do not have our coats I feel the cold air already working on the heavy layer of sweat covering every square inch of my body. I follow Aileen through the knee-deep and sometimes waist-deep snow. It’s wet and I am soaked before I make it a dozen steps, if steps are what one calls it. By the time we make it to the front of the domed building, some hundred yards if you believe Lance, much more if you ask me, I am exhausted and my toes and fingers are frozen. We stand and breath hard for a second and then Aileen bolts for the gate controls. The gates have hardly moved when we are through them and into the main building.

While she makes the call, I sit and pull off my boots and wet socks. By the time two armed individuals rush in and then out, my toes are almost warm again. Just before they go out I say, “If you run into her, don’t turn your back on her. As long as you face her, you are safe.”

They just look at me like, ‘what the hell do you know buddy?’

“The Bengal tiger does not like the human face, cannot stand the sight of it. She’ll back down if you look at her. You do not have to kill her. Just put her down with the dart gun.”

They look at Aileen. She nods her head and they are gone.

In another minute, Victor shows up with Lance. They listen while she explains what happened.

“What were you doing in the Sabre area without Thomas.”

“That’s my fault,” I say. They look at me. “I wanted to observe the sabretooth cats without a bunch of people hanging over me. Just having Ms Bravelli along was enough.”

“You went along with this, Aileen?” Victor says.

“Yes. There was no need for Thomas to be there. What were we going to do? Steal a cat?”

It’s only a glance. But I see it and I understand it. It was the ‘we’ word that did it. ‘What were we going to do,’ she said. Victor’s eyes go briefly between Aileen and me, and in that split second I see his thoughts, and I know he is the one who killed Doctor McCully, and it was because he suspected something between him and Aileen. It’s also in that split second that I know I’ll have to be careful from now on. I could be next.

As a matter of fact, there is no doubt in my mind that there is no doubt in his mind, that I’ll be next. He just needs to figure out how. It won’t be a simple matter of telling Lance to dismiss me. Not at all. He’ll want me here now, more than ever, so that he can keep an eye on me and find the right time.

“You’re right,” he says. “No reason you needed to have Thomas along.” He walks over to the window that faces toward the Bengal garden dome. “What was he doing that she got out? Why did she attack him?”

“I have no idea,” Aileen says.

He looks at me. I shrug my shoulders.

He looks back to Aileen and then back to me again. He isn’t wondering what Thomas was doing. He is wondering how to get me alone in one of the cat or tiger compounds. He is wondering how to make another accident he can just blame on the animals. It won’t be that hard. It already appears the animals are on a rampage.